What Happens When Someone Overdoses on Multiple Drugs?

Most people think of an overdose as taking too much of one drug - maybe too many painkillers or a bad hit of opioids. But in real life, it’s often more complicated. People mix drugs without realizing the danger: opioids with benzodiazepines, pain meds with alcohol, street drugs with prescription pills. When two or more toxic substances hit the body at once, the risks multiply. The body doesn’t handle them one at a time. It tries to process them together - and that’s when things go wrong fast.

In the UK and US, multiple drug overdoses are now the norm, not the exception. According to WHO data, over half of all opioid-related deaths involve at least one other substance, usually benzodiazepines or acetaminophen. A single pill like Vicodin or Percocet already combines an opioid with acetaminophen. Take too many, and you’re not just risking liver failure - you’re also risking stopped breathing. The problem isn’t just quantity. It’s combination.

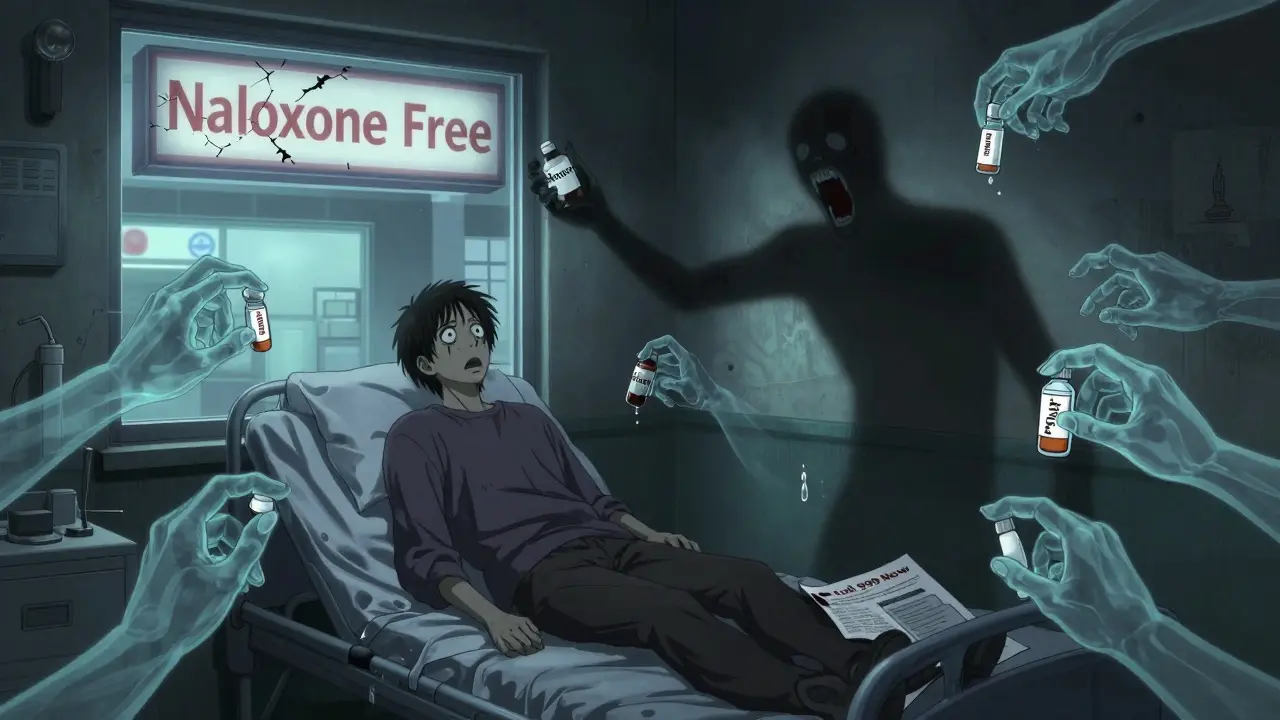

Why Standard Overdose Protocols Often Fail

First responders are trained to give naloxone when someone stops breathing and looks like they’ve overdosed on opioids. That’s life-saving - if the overdose is just opioids. But what if the person also took a large dose of acetaminophen? Or a sleeping pill? Or alcohol?

Naloxone can bring someone back from the brink of respiratory arrest. But it wears off in 30 to 90 minutes. Opioids like fentanyl or extended-release oxycodone can stay in the system for hours longer. If you don’t get to a hospital after naloxone works, the person can slip back into overdose - and this time, no one’s there to help.

Meanwhile, acetaminophen doesn’t cause immediate symptoms. Someone might look fine after being revived with naloxone, but their liver could be silently dying. By the time jaundice or confusion shows up, it’s often too late. The window to give acetylcysteine - the antidote - closes after 8 hours. If you wait for symptoms, you’ve already lost time.

The Critical Role of Naloxone - And Its Limits

Naloxone is the most important tool we have for opioid overdoses. It works by kicking opioids off brain receptors and letting breathing restart. But it’s not magic. In fentanyl overdoses, which are now the most common cause of fatal overdoses in the UK and US, one dose often isn’t enough. SAMHSA’s 2023 guidelines say: if there’s no response after 2-3 minutes, give a second dose. And if the person starts breathing again but then slips back, give more.

That’s why naloxone kits now come with two doses. And why bystanders need training - not just how to inject, but how to keep giving rescue breaths while waiting for it to work. You don’t wait for the drug to kick in. You keep breathing for them until help arrives.

But naloxone does nothing for acetaminophen, benzodiazepines, or alcohol. That’s where things get dangerous. A person might respond to naloxone, breathe again, and be discharged as ‘fine’ - only to develop liver failure 24 hours later. That’s why every suspected overdose needs hospital evaluation, no matter how well they seem to recover.

Acetaminophen Overdose: The Silent Killer

Acetaminophen is in more than 600 medications - cold pills, migraine tablets, prescription painkillers. It’s safe at normal doses. But take more than 10 grams in one go, or keep taking extra doses over days, and your liver starts to die.

The Rumack-Matthew nomogram is the tool doctors use to decide if someone needs acetylcysteine. It’s not about how many pills they took. It’s about blood levels and time. If someone took a massive dose within the last 4 hours, activated charcoal can help pull the drug out of the gut. After that, acetylcysteine is the only thing that works.

Here’s what matters: if the person weighs more than 100 kg, dosing doesn’t go up beyond that. Many hospitals still get this wrong. And if they’re on hemodialysis because their liver is failing, acetylcysteine must be given at 12.5 mg/kg/hour during the procedure. Miss that, and the treatment fails.

For repeated overdoses - taking a few extra pills every day for a week - the rules change. If liver enzymes are rising or acetaminophen levels are above 20 μg/mL, give acetylcysteine anyway. Don’t wait for the nomogram line to be crossed. The damage is already starting.

When Drugs Mix: The Most Dangerous Combinations

Some combinations are deadly by design. Here’s what you need to know:

- Opioid + Acetaminophen (Vicodin, Percocet): Naloxone + acetylcysteine must be given together. Watch for rebound respiratory depression after naloxone wears off.

- Opioid + Benzodiazepine (oxycodone + diazepam): This is one of the deadliest mixes. Flumazenil can reverse benzodiazepines - but if the person is dependent, it can trigger violent seizures. Many ERs avoid it entirely.

- Tramadol + Other Drugs: Tramadol isn’t a classic opioid, but it still causes respiratory depression. It needs naloxone - and often multiple doses or an IV drip because it lasts 5-6 hours.

- Alcohol + Any Sedative: Alcohol makes every other drug more toxic. It slows metabolism, increases sedation, and raises the risk of aspiration. No antidote exists.

There’s no single protocol for every mix. Each case needs a custom plan. That’s why hospitals now use toxicology teams - not just ER doctors - to manage these cases. One person handles breathing, another tracks liver enzymes, a third monitors for seizures. Coordination saves lives.

What Happens After the Emergency?

Surviving a multiple drug overdose doesn’t mean you’re out of danger. The physical damage can last for months. Liver damage from acetaminophen can lead to chronic scarring. Brain damage from oxygen loss can cause memory problems or depression. And the risk of another overdose? It’s extremely high.

WHO and SAMHSA both stress: after resuscitation, the patient must be connected to long-term care. That means counseling, medication-assisted treatment (like methadone or buprenorphine), and regular check-ins. People released from prison are at the highest risk - 40 times more likely to die of overdose in the first four weeks. That’s not just a statistic. It’s a failure of the system.

Follow-up with a primary care doctor is non-negotiable. They need to check liver function, kidney health, and mental state. And they need to talk about why the overdose happened. Was it pain? Trauma? Isolation? Addiction? Without addressing the root cause, another overdose is almost guaranteed.

What Can You Do - As a Bystander or Family Member?

You don’t need to be a doctor to save a life. Here’s what works:

- Call 999 immediately. Don’t wait. Don’t try to handle it alone.

- Give naloxone if you have it. Even if you’re not sure it’s opioids. It won’t hurt someone who didn’t take them.

- Keep breathing for them. Rescue breaths can keep oxygen flowing until paramedics arrive.

- Stay with them. Even if they wake up, don’t let them go to sleep. Monitor them for 4 hours after naloxone.

- Know the signs of acetaminophen overdose. Nausea, vomiting, sweating, pain under the ribs - these can show up hours later. If they took any painkiller, get them to the hospital.

Keep a naloxone kit at home if you or someone you care for uses opioids, benzodiazepines, or painkillers. They’re free in many UK pharmacies. Training takes 10 minutes. It could be the difference between life and death.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Multiple drug overdoses aren’t going away. They’re getting worse. Fentanyl is stronger. Painkillers are more widely prescribed. Mental health crises are rising. The only way forward is to treat overdoses not as moral failures - but as medical emergencies that need better systems.

Hospitals need toxicology teams. Pharmacies need to stock naloxone without a prescription. Communities need training. And we all need to stop pretending overdoses only happen to ‘other people.’ They happen to neighbours, coworkers, family members - people who just needed help and didn’t know how to ask.

The tools exist. The knowledge exists. What’s missing is the will to act - before the next person stops breathing.

i saw a guy collapse at the gas station last month. i gave him the naloxone i kept in my glovebox. he woke up, smiled, and walked away. i didn’t know if he’d take another hit tomorrow but i knew i did what i could.

we need more of these kits everywhere. not just for ‘addicts’ - for people.

OMG this is literally the most important thing i’ve read all year 😭😭😭 someone needs to make a TikTok series out of this. like, imagine if the whole world had to watch this before they could get a prescription for Xanax? 🤯

The pharmacokinetic interactions here are non-trivial - particularly the CYP450 enzyme inhibition from concurrent benzodiazepine and alcohol use, which significantly prolongs the half-life of opioids via reduced hepatic clearance. Also, acetaminophen’s glutathione depletion threshold is dose-dependent and nonlinear, meaning the Rumack-Matthew nomogram has limited sensitivity in polypharmacy cases unless serum levels are serially tracked.

I want to say thank you for writing this with such care and precision. This isn’t just medical information - it’s a lifeline for families who’ve lost someone, for nurses who work double shifts, for friends who don’t know what to do when someone stops breathing.

The way you explain that naloxone isn’t a cure - it’s a bridge - that’s the kind of clarity we need in public health. No one should be shamed for needing help. No one should be left alone after revival. We are all responsible for each other’s survival.

they keep saying naloxone saves lives but no one talks about how the system just dumps you back on the street after 4 hours and wonders why you OD again

if you care about overdoses fix the housing fix the trauma fix the poverty fix the mental health care stop acting like a pill and a breath is enough

This is so important. My cousin survived a triple overdose last year - opioids, benzos, and acetaminophen. They let him go home after 6 hours because he ‘looked fine.’ Three days later he was in the ICU with liver failure.

Please share this. Everyone needs to know: if they took ANY painkiller, even one, and they passed out - they need to go to the hospital. No exceptions.

in south africa we dont have naloxone in most pharmacies but people still mix dagga and prescription meds all the time. its quiet but deadly. i wish more people knew how simple it is to carry two doses. no drama just life

I’ve worked in ERs across three continents and this is the most accurate summary I’ve seen. In Nigeria, we see a lot of tramadol + alcohol combos - people think it’s just a ‘strong painkiller’ but it’s a silent respiratory depressant. The same rules apply: if they’re unconscious, give naloxone, keep breathing, get them to a hospital.

And yes - the liver damage from acetaminophen? It doesn’t care if you’re rich or poor. It just kills.

You know who’s really behind this? The pharmaceutical companies. They’ve been pushing combo pills for decades - Vicodin, Percocet, you name it - because they make more money selling two drugs in one tablet. Then when people overdose, they say it’s ‘user error’ - but they designed the system to make it easy to accidentally kill yourself.

And don’t get me started on the FDA. They approved fentanyl patches with no safety caps, no warnings about mixing with alcohol, and now thousands are dead. This isn’t an epidemic - it’s corporate negligence. The government knew. They just didn’t care.

You think they’re going to fix it? No. They’ll keep selling the next ‘safe’ painkiller. And the next. And the next. Until the whole system collapses under its own greed. We’re not victims. We’re collateral damage in a profit machine.

I just spent 3 hours reading this like it was a thriller novel... and I’m crying. Not because it’s sad - because it’s so obvious and yet NO ONE talks about it like this.

WHY ISN’T THIS ON EVERY HIGH SCHOOL HEALTH CURRICULUM?!?!?!

Also, if you’re reading this and you have a loved one on opioids - go to your pharmacy RIGHT NOW and ask for naloxone. Don’t wait. Don’t think ‘it won’t happen to us.’ It already has. It’s already happening.

The real tragedy isn’t the overdose - it’s the silence that precedes it. People don’t die because they took too much. They die because they were too afraid to ask for help. Too ashamed to say they were in pain. Too alone to believe anyone would care.

We treat addiction like a moral failure because it’s easier than confronting our collective failure to care. We build hospitals but not homes. We give pills but not purpose. We revive bodies but leave souls to rot.

Until we stop seeing addicts as problems and start seeing them as people - we will keep burying them.

I’m a nurse in a rural ER. We don’t have a toxicology team. We have one overworked doctor and a handful of nurses trying to track three different overdoses at once.

This post? It’s our bible. We print it out and hang it by the crash cart. We teach families how to use naloxone. We beg them to stay for observation. We cry when they leave because we know they’re probably going to die.

Thank you for writing this. You gave us words we can use when we don’t have time to explain.

In my village in Nigeria, we call this 'the silent death that walks with medicine'. People do not understand that a tablet from the pharmacy can be as deadly as street drugs. We teach our youth: 'If your body feels heavy after taking pills, even if you feel fine - go to the clinic. Do not wait for the world to notice you are dying.'

We do not have naloxone, but we have neighbors. We have hands that hold, voices that shout, and hearts that refuse to look away. This is not just an American problem - it is a human one. And we are all part of the solution.