Most people who breathe in tuberculosis bacteria never get sick. That’s not because the bacteria are harmless-it’s because their immune system locks them away. This hidden form is called latent TB infection. But for some, those dormant bacteria wake up. When they do, they cause active TB disease-a serious, contagious illness that can destroy lungs and spread to others. The difference between these two states isn’t just medical jargon; it’s the difference between living with a silent threat and fighting a full-blown infection. And how you treat each one? Totally different.

What Is Latent TB Infection?

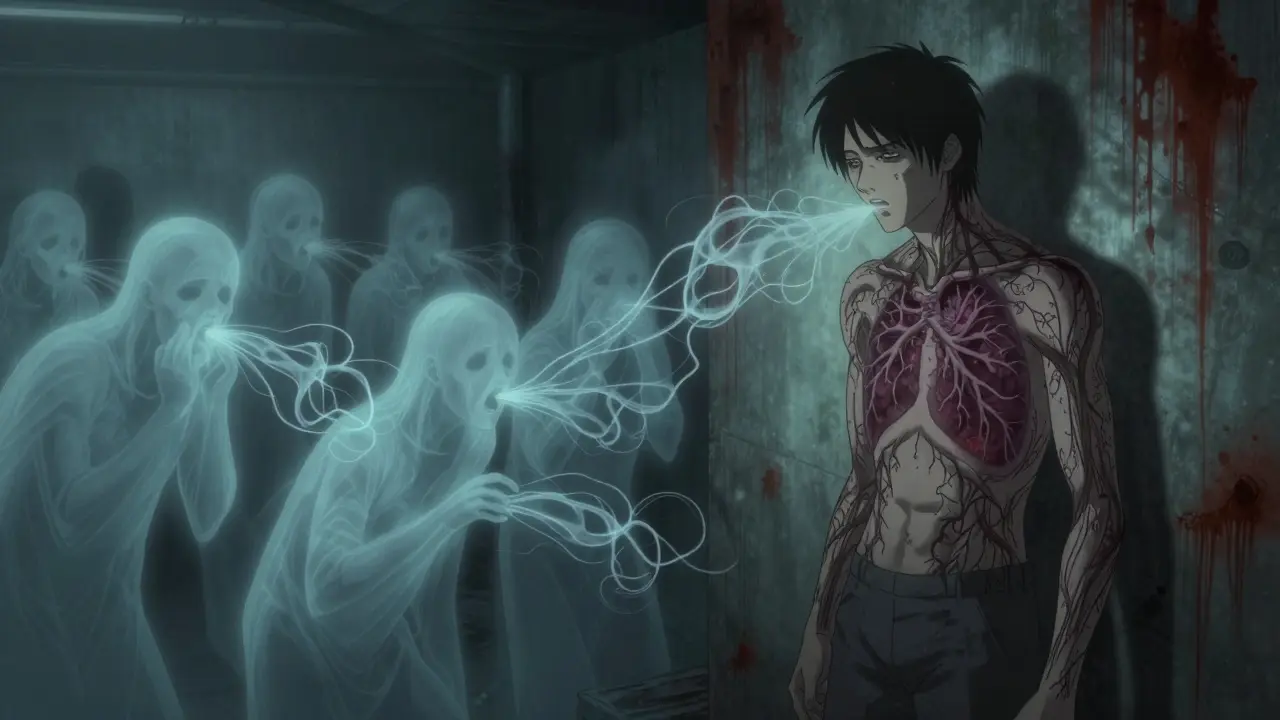

Latent TB means you’ve been infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, but your body has contained it. The bacteria are alive, tucked inside granulomas-tiny clusters of immune cells that wall them off. You feel fine. You don’t cough. You can’t spread it to anyone. No fever. No weight loss. No night sweats. That’s why so many people don’t know they have it.

How do you find out? A positive tuberculin skin test (TST) or an interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) blood test. Both detect your immune system’s memory of the bacteria. A chest X-ray will look normal. Sputum tests come back negative because there’s no active multiplication. The CDC says this state can last decades. For most people, it stays that way. But for about 5-10% of those infected, the bacteria eventually break free.

Why does that happen? It’s not random. Your immune system weakens-maybe from HIV, diabetes, kidney failure, or just aging. People on immunosuppressants for organ transplants or autoimmune diseases are at higher risk. The Georgia Department of Public Health found that someone with untreated HIV is 20 to 30 times more likely to develop active TB than someone with a healthy immune system. That’s why testing and treating latent TB in high-risk groups isn’t optional-it’s life-saving.

What Happens When TB Becomes Active?

Active TB is when the bacteria multiply, break out of their cages, and start damaging tissue. The lungs are the usual target-pulmonary TB-but the infection can spread to bones, kidneys, the brain, even the spine. Symptoms don’t show up overnight. They creep in over weeks: a cough that won’t quit, fatigue that doesn’t lift, night sweats so heavy you need to change your pajamas, and unexplained weight loss. Fever comes and goes. Some people cough up blood.

According to the Mayo Clinic, these symptoms often start mild and get worse slowly. That’s part of why TB gets missed. People think it’s just a lingering cold. Or they’re too busy to see a doctor. But if you’ve had a cough for more than three weeks, especially if you’ve been around someone with TB or came from a country where TB is common, you need testing.

Diagnosis isn’t just about symptoms. You need sputum tests-microscopic exams and cultures-to find the bacteria. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) can give results in hours, detecting TB DNA in coughed-up mucus. A chest X-ray usually shows patches, holes, or scarring in the lungs. Unlike latent TB, active TB is contagious. Every cough, sneeze, or even loud talk can send infectious droplets into the air. In crowded, poorly ventilated spaces-like shelters, prisons, or refugee camps-it spreads fast.

How Are Latent and Active TB Treated Differently?

Latent TB doesn’t need to be treated right away-but it should be. The goal isn’t to cure an illness; it’s to prevent one. The standard treatment is nine months of isoniazid. That’s a lot of pills. Many people stop before finishing, which is why shorter regimens are now preferred. The CDC and WHO now recommend three months of weekly isoniazid and rifapentine. That’s just 12 doses. Or four months of rifampin alone. These options are easier to stick with-and they work just as well.

Active TB? That’s a full-on medical battle. You need at least four antibiotics at once for the first two months: isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. This combo kills the bacteria fast and stops resistance from developing. After that, you drop two drugs and keep isoniazid and rifampin for another four to seven months. Total treatment: six to nine months. No shortcuts.

Why so long? TB bacteria multiply slowly. Antibiotics that kill fast-growing bugs don’t work well here. You have to keep hitting them for months until every last one is gone. Miss a dose? Skip a week? That’s how drug-resistant TB starts. Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) is harder to treat, takes up to 20 months, and costs 100 times more than standard therapy.

That’s why directly observed therapy (DOT) is standard. A nurse or community health worker watches you swallow each pill. It’s not about control-it’s about success. Studies show DOT cuts treatment failure and relapse by half. In the UK, DOT is routine for all active TB cases. In the U.S., it’s recommended for everyone, especially those with HIV, homelessness, or a history of non-adherence.

Side Effects and Monitoring

TB drugs are powerful-and they can hurt your liver. Isoniazid and rifampin are the biggest culprits. You might feel nauseous, get yellow eyes or skin, or notice dark urine. That’s not normal. You need liver function tests before you start and every few weeks while on treatment. Your doctor will tell you to stop the meds and call immediately if you see these signs.

Pyrazinamide can cause joint pain. Ethambutol can affect vision-rarely, but it happens. If you notice blurred vision or trouble seeing colors, tell your doctor right away. You might need an eye exam. These side effects are manageable, but only if caught early.

And yes, you’ll need to avoid alcohol. It increases liver damage risk. Some people also need vitamin B6 supplements with isoniazid to prevent nerve problems. It’s not just about taking pills-it’s about managing your whole health while you’re on them.

Why Latent TB Matters More Than You Think

Here’s the hard truth: most new TB cases come from people who already had latent infection. Not from new exposures. That’s why public health programs focus on testing high-risk groups: immigrants from countries with high TB rates, people living with HIV, those in homeless shelters, healthcare workers in high-burden areas. Treating latent TB in these groups is the most effective way to reduce overall TB numbers.

In the U.S., TB cases hit a record low in 2020-just 2.2 per 100,000 people. But that number hides the truth: 80% of cases were in foreign-born individuals. Many of them were infected years ago, in their home countries, and only now show signs. Without latent TB screening and treatment, those cases would keep coming.

Global progress is slow. TB incidence drops only about 2% per year. Meanwhile, drug resistance grows. The WHO still calls TB a global emergency. But progress is possible. In 2023, the WHO endorsed shorter, simpler regimens for latent TB. Countries like Canada and Australia have cut TB rates by 50% in a decade by targeting latent infection in immigrant populations. It’s not magic. It’s strategy.

What Comes Next?

Research is moving fast. Scientists are looking for blood tests that can tell if latent TB is about to become active-before symptoms appear. They’re testing new drugs that kill TB faster, even resistant strains. One promising drug, pretomanid, is already part of new six-month regimens for MDR-TB. And vaccines? The old BCG shot doesn’t work well in adults. New ones are in trials, including one that’s showing promise in preventing latent TB from turning active.

But for now, the tools we have work-if we use them. Test people at risk. Treat latent TB. Watch people on active TB treatment. Don’t let them miss doses. Keep the air moving in crowded places. Educate communities. TB isn’t gone. But it’s beatable.

Can you have latent TB and never develop active disease?

Yes. Most people with latent TB never develop active disease. About 90-95% of infected individuals carry the bacteria for life without symptoms. Their immune system keeps it under control. But the risk never fully disappears, especially if their immune system weakens later in life due to illness, aging, or medication.

Is latent TB contagious?

No. Latent TB is not contagious. You cannot spread it to others through coughing, sneezing, or close contact. The bacteria are inactive and contained. Only active pulmonary TB-where bacteria are multiplying in the lungs-can be spread through airborne droplets.

How long does TB treatment take?

Latent TB treatment usually lasts 3 to 9 months, depending on the drug regimen. Active TB requires at least 6 months of multiple antibiotics. For drug-resistant TB, treatment can take 9 to 20 months. Completing the full course is critical to prevent relapse and drug resistance.

Can you get TB again after being treated?

Yes. Being treated for TB doesn’t make you immune. You can be reinfected with a new strain of the bacteria. That’s why people in high-risk areas or with ongoing exposure should remain aware of symptoms, even after successful treatment. Reinfection is more common than relapse in places with high TB rates.

Do I need to isolate if I have latent TB?

No. If you have latent TB, you do not need to isolate. You are not contagious and can continue normal activities-work, school, socializing-without restrictions. Isolation is only required for people with active, infectious pulmonary TB until they’ve been on treatment for at least two weeks and are no longer contagious.

What happens if I stop taking my TB meds early?

Stopping early can lead to relapse and drug-resistant TB. The bacteria that survive become harder to kill. Multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) requires longer, more toxic, and expensive treatment. In some cases, it becomes untreatable. Always finish your full course-even if you feel better.

What to Do If You’re at Risk

If you came from a country where TB is common-like India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Nigeria, or Pakistan-get tested. If you live or work in a shelter, prison, or healthcare setting, get tested. If you have HIV or are starting immunosuppressive therapy, get tested. A simple skin or blood test can save your life-or someone else’s.

Don’t wait for symptoms. Latent TB doesn’t have any. And if you’re diagnosed, don’t delay treatment. The pills are long, the side effects are real, but the alternative-active TB-is far worse. You don’t need to be a doctor to understand this: catching TB early, whether latent or active, is the only way to stop it from spreading.

So let me get this straight-we’re paying people to take pills for a disease they don’t even have, just in case it wakes up one day like a sleepy bear? And if they skip a dose, we call it a public health crisis? I mean, I get it, but wow. The bureaucracy of prevention is wild.

Still, I’d rather take 12 pills over 3 months than spend 9 months coughing up blood while my landlord wonders why I’m always late on rent. TB doesn’t care about your schedule. It just waits.

It is imperative to underscore the significance of early detection and adherence to prescribed regimens in the management of tuberculosis. The distinction between latent and active infection is not merely clinical-it is a foundational element of epidemiological control. Public health initiatives that prioritize screening in high-risk populations represent a scientifically sound and ethically responsible approach to disease mitigation.

Furthermore, the implementation of directly observed therapy remains one of the most effective interventions in reducing transmission and preventing the emergence of drug-resistant strains. Consistency in treatment is not optional; it is non-negotiable.

They give you a pill for a ghost. A ghost that might wake up if you get sick, or old, or just stop caring about your health. Meanwhile, the same people who push this ‘preventive’ nonsense won’t give you a free MRI for your back pain.

But hey, if taking a pill every week for three months stops you from becoming a human coughing volcano later, I guess it’s worth it. Just don’t tell me it’s ‘medicine.’ It’s insurance against your future self being dumb.

USA think they own TB science now? 😂 We in Nigeria have been fighting this since the 80s with no fancy NIH funding-just faith, garlic, and mama’s herbal tea.

But yes, your 3-month pill plan? Cute. We use ‘Tuberculin’ like a curse word here. When someone coughs too long? We say, ‘E be like TB dey follow am!’ 😎

And if you stop taking pills? You don’t get drug-resistant TB-you get *village legend status*. People whisper your name like a warning. ‘Baba, don’t be like Ola-he stopped his pills and now he talks to ghosts in the hospital.’ 🕯️

Respect the science, but don’t forget: African lungs don’t need WHO to tell them how to survive.

I’ve worked in homeless shelters for 12 years. I’ve seen people ignore TB symptoms because they didn’t have a place to shower, let alone a calendar to track pills.

DOT-directly observed therapy-isn’t just ‘good practice.’ It’s survival. I’ve watched nurses sit with guys for 10 minutes every day, just to make sure they swallowed that pill. No judgment. Just presence.

One guy, James, finished his 9-month regimen and got a job at a auto shop. He still comes in once a month to say thanks. He didn’t just get cured-he got his life back.

If you think this is about pills, you’re missing the point. It’s about people. And if you’re not willing to show up for them, then don’t act surprised when the disease wins.

Latent TB: silent. Active TB: contagious. Treatment: long. Side effects: real. But the alternative? Worse.

Get tested. If you’re at risk, don’t wait. Done.

It is of paramount importance to recognize that adherence to the full course of antitubercular therapy constitutes a critical public health imperative. Non-compliance not only jeopardizes individual outcomes but also directly contributes to the global proliferation of multidrug-resistant strains, which are increasingly untreatable and economically unsustainable.

Healthcare providers must therefore prioritize patient education, structural support, and consistent monitoring. The burden of disease cannot be alleviated through pharmacological intervention alone; it demands systemic, compassionate, and coordinated engagement.

Let us not underestimate the gravity of this ongoing global health challenge.

So… I got tested last year because I worked at a clinic. Turned out latent. Took the 3-month combo. No big deal. Took my pills with my coffee.

Now I’m just waiting for the government to send me a medal or a free smoothie. 🤷♀️

Also, my mom said I should’ve used garlic. I told her garlic doesn’t kill bacteria, it just makes your breath smell like regret. She didn’t talk to me for a week.

Okay but… what if the ‘latent’ TB is actually a government tracking chip disguised as bacteria? 🤔

I mean, why do they care so much about people who don’t even have symptoms? Why not just let nature take its course? Or… is this about controlling the population? 🤐

And why is it always ‘high-risk groups’? Why not test everyone? Hmm. Why is the CDC pushing ‘shorter regimens’? Shorter means less data collection, right? Or… are they hiding something?

Also, I read that rifampin turns your pee orange. That’s not medicine. That’s a warning sign. Like… your body is screaming. And nobody’s listening.

They say ‘finish your pills.’ But what if the pills are the problem? What if the real cure is… not taking them?

Just saying. I’m not anti-science. I’m pro-awake. 🕵️♀️🧪

P.S. My cousin’s neighbor’s dog had TB. No joke. I swear. The vet said it was ‘zoonotic.’ So… are we being infected by dogs now? Or is this all a lab leak?