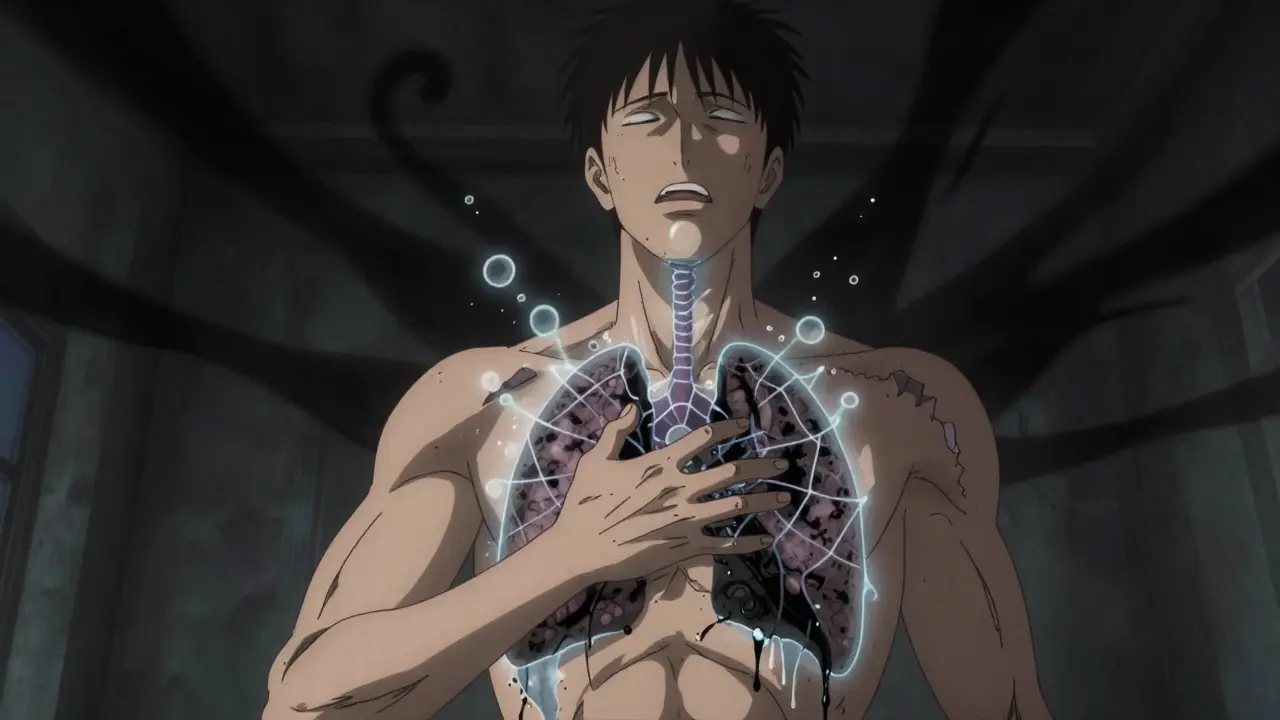

When your lung suddenly stops working properly, it’s not something you can ignore. A pneumothorax is a condition where air leaks from the lung into the space between the lung and chest wall, causing the lung to collapse. This isn’t just a minor discomfort-it’s a medical emergency that can turn deadly in minutes if not handled correctly.

What Does a Collapsed Lung Feel Like?

The first sign is often a sharp, stabbing pain on one side of your chest. It doesn’t come and go. It hits hard, especially when you breathe in or cough. People describe it like being stabbed with a knife, and the pain often shoots into the shoulder on the same side. This isn’t just muscle strain or heartburn. It’s the lung pulling away from the chest wall, and your body knows something’s wrong.

Right after the pain, most people start struggling to breathe. Not just a little out of breath-this is when even sitting still feels like running a marathon. About 9 out of 10 people with pneumothorax report shortness of breath. If more than 30% of your lung has collapsed, you’ll feel it even at rest. If it’s smaller, you might only notice it when climbing stairs or walking fast.

Doctors look for three clear signs during an exam: no breath sounds on the affected side, a hollow, drum-like sound when tapping the chest (called hyperresonance), and reduced vibration when placing a hand on the chest (tactile fremitus). These aren’t guesses-they’re measurable, repeatable findings backed by data from emergency departments across the U.S. and Europe.

When It Turns Deadly: Tension Pneumothorax

Not all collapsed lungs are the same. The worst kind is called tension pneumothorax. This happens when air keeps entering the chest cavity but can’t escape. It builds pressure like a balloon filling up, and soon it’s pushing your heart and other lung sideways.

Here’s what happens next: your heart rate spikes above 134 beats per minute. Your blood pressure drops below 90. Your oxygen levels fall below 90%-even if you’re sitting still. Your lips or fingertips might turn blue. You might start gasping for air and can’t speak in full sentences. In the most severe cases, your windpipe shifts away from the side of the injury. But here’s the catch: that last sign only shows up in about one-third of cases. Waiting for it means waiting too long.

Every second counts. The American Heart Association says if you see someone with these signs, don’t wait for an X-ray. You need to act immediately. Needle decompression-inserting a needle into the chest to release the trapped air-can save a life in under two minutes.

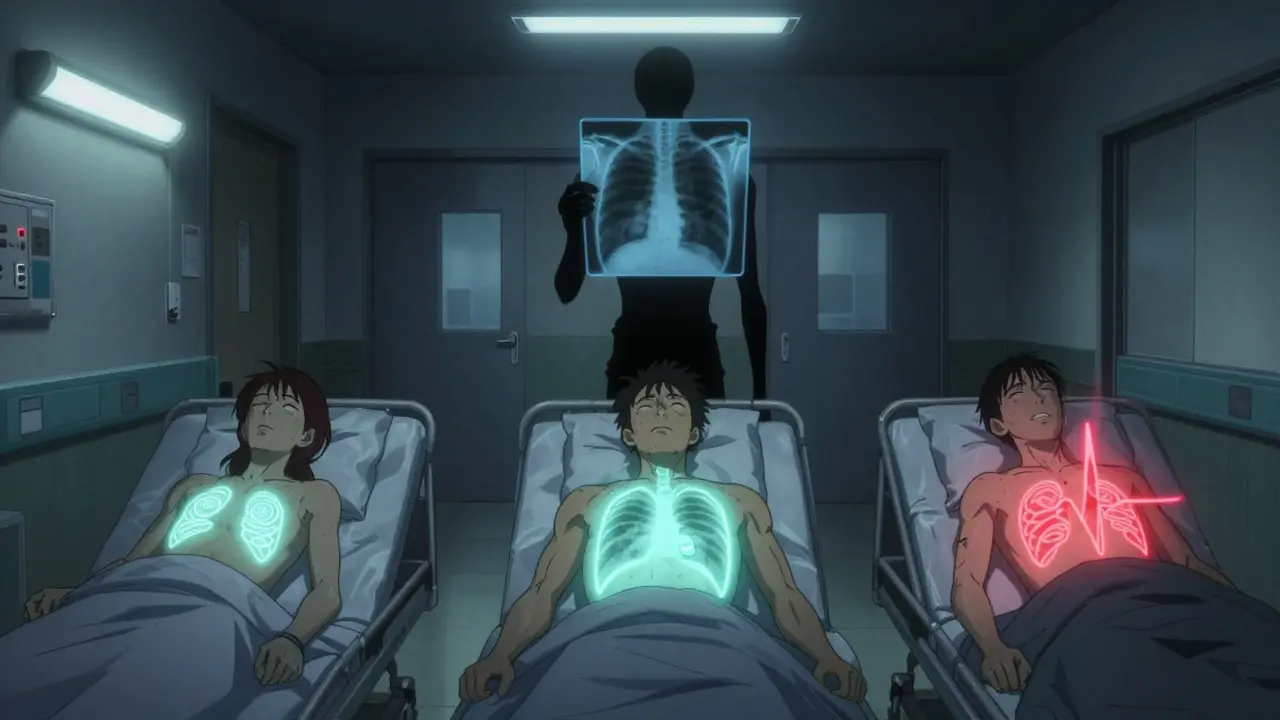

How Doctors Diagnose It

Most hospitals start with a chest X-ray. It’s fast, cheap, and catches 85-94% of cases. But if you’re lying down after a car crash, the X-ray might miss it. In trauma settings, emergency teams now use ultrasound-the E-FAST scan. A trained provider can spot a pneumothorax with 94% accuracy by watching for the "lung point," a tiny spot where the lung still moves against the chest wall. It’s like watching a flag flap in the wind-when the lung collapses, the flag stops moving.

CT scans are the gold standard. They can see as little as 50 milliliters of air-about the size of a golf ball. But they take time, cost more, and expose you to radiation. So they’re used when the X-ray is unclear or if the patient has other injuries.

Blood tests also help. A low oxygen level (PaO₂ under 80) and low carbon dioxide (PaCO₂ under 35) are common. These aren’t diagnostic on their own, but they tell doctors the body is struggling.

Treatment: What Happens in the ER

Not every collapsed lung needs a tube stuck in your chest. If the collapse is small-less than 2 cm on the X-ray-and you’re breathing okay, doctors might just watch you. Oxygen helps. Breathing pure oxygen speeds up how fast the body reabsorbs the air. With oxygen, the air disappears 3-4 times faster than normal. About 8 out of 10 small cases heal on their own within two weeks.

For bigger collapses, they’ll try needle aspiration. A thin tube is inserted into the chest and air is sucked out with a syringe. It works in about two-thirds of cases. If that fails, or if you’re in serious distress, they’ll insert a chest tube. A 28F tube (about the thickness of a pencil) is threaded between your ribs to drain the air. This works in 92% of cases but can cause pain, infection, or even fluid buildup in the lung after it re-expands.

For people who’ve had this happen before, surgery might be the best option. A video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) lets the surgeon seal the leak and remove part of the lung lining. It cuts recurrence risk from over 40% down to just 3-5%. But it means a few days in the hospital and a bill around $18,500 in the U.S.

Who’s at Risk?

Most cases happen in young, tall men-often with no other health problems. That’s called primary spontaneous pneumothorax. But if you have lung disease like COPD, emphysema, or cystic fibrosis, your risk jumps. Secondary pneumothorax (linked to disease) is far more dangerous. One in six people with this type die within a year.

Smoking is the biggest preventable cause. If you smoke more than 10 pack-years (that’s one pack a day for 10 years), your risk is over 20 times higher than a non-smoker. Quitting cuts your chance of it happening again by 77% in the first year.

Other risks include tall height (over 70 inches), male gender, and family history. If you’ve had one, you have a 15-40% chance of having another within two years. And if you’ve had two on the same side? Your chance of a third jumps to 62%.

What to Do After You Leave the Hospital

Going home doesn’t mean you’re out of the woods. You need follow-up. A chest X-ray at 4-6 weeks confirms your lung fully re-expanded. Skip this, and 8% of people develop complications later.

Avoid flying for 2-3 weeks. Changes in cabin pressure can cause the air to expand again. And never scuba dive unless you’ve had surgery to prevent recurrence. The risk of another collapse underwater is over 12%.

Watch for warning signs: sudden return of sharp chest pain, blue lips, or being unable to speak a full sentence. These mean call 999 (or 911) immediately. Don’t wait. Don’t drive yourself. Time is everything.

Prevention Is Possible

The best way to avoid a second pneumothorax? Stop smoking. That’s it. No magic pills, no special diets. Just quitting. Studies show it’s the single most effective thing you can do.

If you’ve had multiple episodes, talk to a thoracic surgeon. VATS surgery isn’t just for the severely ill-it’s for anyone who wants to live without fear of another collapse. And if you’re a young man who’s tall and smokes? You’re in the highest-risk group. Talk to your doctor now, before it happens.

Can a collapsed lung heal on its own?

Yes, but only if it’s small. If the lung collapse is less than 30% and you’re not having trouble breathing, doctors often just give you oxygen and watch. About 82% of these cases heal naturally within two weeks. But if the collapse is larger or you’re struggling to breathe, you’ll need treatment-no waiting.

Is pneumothorax the same as a pulmonary embolism?

No. A collapsed lung (pneumothorax) is air leaking out of the lung into the chest cavity. A pulmonary embolism is a blood clot blocking an artery in the lung. Both cause chest pain and shortness of breath, but they’re treated completely differently. A clot needs blood thinners; a collapsed lung needs air removed.

How long does it take to recover from a pneumothorax?

Recovery time depends on treatment. If it’s small and watched, you’ll feel better in 1-2 weeks. With a chest tube, you’re usually in the hospital for 3-5 days and need 2-4 weeks to return to normal activity. After surgery, most people go home in 2-4 days and return to work in 3-6 weeks. Full lung healing can take up to 6 months.

Can you exercise after a collapsed lung?

Not right away. Avoid heavy lifting, intense cardio, or contact sports for at least 4-6 weeks. Your lung needs time to heal. If you had surgery, your doctor will give you a timeline. Returning too soon increases the risk of recurrence. Always get clearance before resuming exercise.

Why does smoking increase the risk so much?

Smoking damages the tiny air sacs in the lungs (alveoli), making them weak and prone to rupture. It also causes inflammation and changes lung pressure patterns. Studies show smokers are 22 times more likely to have a spontaneous pneumothorax than non-smokers. Quitting cuts that risk dramatically-even after just one year.

Final Thoughts

Pneumothorax doesn’t care who you are. It can strike a fit 20-year-old athlete or a 70-year-old with COPD. But the outcome? That’s up to you. Know the signs. Act fast. Quit smoking. Get follow-up care. These aren’t just medical tips-they’re survival steps. In emergency medicine, seconds matter. In life, they matter even more.

I read this whole thing and honestly? Too much info. I just want to know if I should panic when my chest hurts. Why does everything have to be a textbook?

Also who the hell has time to get a CT scan after a bad cough?

This is actually really helpful. I had a friend go through this last year and I had no idea what was going on. The part about oxygen speeding up reabsorption? That’s wild. I never thought breathing pure O2 could make that much of a difference. Good job breaking it down without being scary.

Man I remember when I got pneumothorax in uni I was 63 and smoked 2 packs a day for 8 years

Woke up with pain like a knife in my side thought it was a pulled muscle

Turns out I was half collapsed and they had to stick a tube in

Quit smoking after that and never looked back

Also dont fly for 3 weeks I tried and nearly died again

85-94% accuracy on X-rays? That’s not good enough. I’ve seen cases where pneumothorax was missed for days because the tech didn’t rotate the patient properly. And ultrasound? It’s all about who’s holding the probe. One guy’s trained, another’s barely watched a YouTube video. This isn’t science, it’s a gamble with your lungs.

I’m so glad this exists. My sister had a spontaneous collapse last winter. She was terrified. I wish I’d known about the oxygen speeding up healing - it would’ve calmed her down so much. Thank you for explaining what recovery actually looks like. So many people think it’s just rest, but there’s real science behind it.

I’m from Australia and we see a lot of this in surfers and climbers. The altitude changes and sudden pressure shifts make it way more common than people think. Also, the smoking stats are insane. My cousin had three episodes before he quit - now he’s hiking Kilimanjaro. Quitting isn’t easy but it’s the only thing that really works.

They say 'quit smoking' like it's the magic bullet. But what about the 15% of cases in non-smokers? What about the ones with no family history and no tall frame? This article makes it sound like it's all preventable. Bullshit. It's just luck. And now they want you to pay $18,500 for surgery? 😂

I dunno maybe im just old but back in the day we just lay down and waited for the air to go away

now its needles and tubes and scans and bills

im not saying its bad just... weird how we went from 'rest and breathe' to 'emergency thoracic intervention' in 30 years

also i think the lung point thing is kinda poetic

The clinical details here are precise and well-sourced. I appreciate the distinction between primary and secondary pneumothorax, especially the mortality data. For those considering surgery, VATS is not merely a 'last resort'-it is a definitive intervention that restores autonomy. Follow-up imaging is non-negotiable. And yes, oxygen therapy is physiologically superior to passive observation in small cases. This is evidence-based medicine at its clearest.